Towards A New Net Art

I.

Imagine a network, nodes connected by links, cables running across oceans, circuit boards flashing; picture the internet as back end infrastructure, as the dystopian grids and matrices of Gibsonian “cyberspace” and its nineteen-nineties insurrectionists, teenage hackers. This is not yet a spiritual network, not yet characterized by connections of love and friendship, only a sped-up means of information exchange, a time-lapse of city traffic, a virtual filing cabinet vulnerable to invisible thieves. In popular depictions during its nascent decade, the internet could scarcely be distinguished from the effects of amphetamine, a connection confirmed by the speed-addled theorists of the Cybernetic Culture Research Unit in Leamington Spa. Art is insurrection, said its greatest member, Nick Land; it is breaking the law.[1] Thus imagine the network achieving escape velocity, subverting its original bureaucratic intention and becoming autonomous, finding a purpose fit to its nature—imagine being part of its glorious creation, a cathedral for the age, artists lining up to decorate its ceilings.

II.

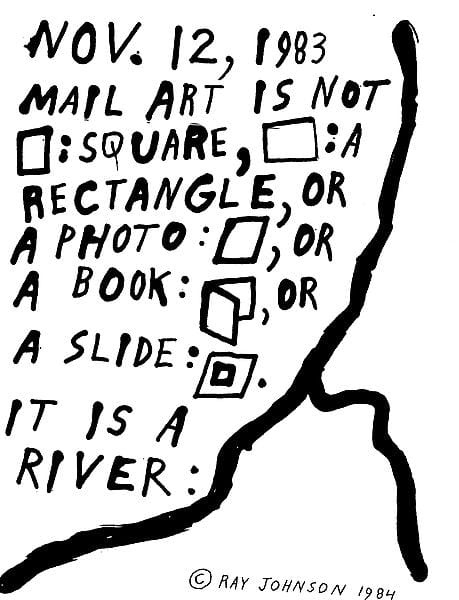

The postal service was perhaps the first network to be wrestled from its utilitarian correspondence function, its transmission of bills and notices and letters home. Ray Johnson’s mail art can be said to be the earliest precursor to net art, if not strictly chronologically then at least technologically, using a network in which messages are recorded on tangible media (usually paper) and transported using locomotion rather than as electromagnetic signals. Starting in the mid-fifties, Johnson began mailing out what he called ‘moticos’ (an anagram for osmotic)[2] to a network of friends and colleagues. The aesthetics of Johnson’s moticos, as the name suggests, used the detritus of print media—the front cover of ArtForum, postcards, fashion spreads, ‘found images’—overlayed with handwriting, doodles,[3] Warholian screen printing, and dual layer photocopying. The early pieces are credited as being some of the first examples of pop art in their incorporation of industrial commodities and mechanized production techniques. Like Warhol’s factory a decade later, Johnson’s practice and aesthetics allowed his artistic output to scale exponentially, growing beyond its initial sphere of recipients into the far-ranging New York Correspondence School, whose central tenet was the emphasis on process over product. Like the Simple Net Art Diagram (1997) by MTAA, which points to the wire connecting two computers and proclaims ‘The art happens here,’ the aesthetic value of mail art cannot be separated from its distribution practice: a motico only becomes mail art if it’s posted. As Johnson said himself in 1984 ‘Mail Art is not square, a rectangle, or a photo, or a book, or a slide. It is a river.’[4]

III.

There has been an artistic side to the internet since before the inception of the World Wide Web protocol in 1990. Before net art, there was telecommunication art such as practiced by Robert Adrian X. Adrian X was one of the originators of Artex, the first electronic mail system for artists, a precursor to mailing lists such as nettime, Rhizome, and the forums and group chats of today. These early net artists, while often employing pseudonyms, met in the media labs and universities from which the internet was primarily accessible before widespread adoption. It was a high-latency, low-bandwidth world of dial-up modems and clogged up phone lines. Adrian X described the internet as a structure of cables, servers, computers, software, and people organized in spatial dimensions. Others were preoccupied with mapping out the web of hyperlinks at a time before ubiquitous search indexing. Throughout the nineties, net artists engaged in, among other things, media hacking (‘using low-tech tools to reach very large audiences’), spam art, spoof websites impersonating large corporations, creative hyperlinking, and glitch art. Some specific examples: Jodi’s website art (such as Automatic Rain (1995) and the still extant Jodi.org), Alexei Shulgin’s ‘web rings’ and ‘art loops’, Brett Stalbaum’s FloodNet (software that bombarded specific websites with requests on the model of a ‘sit in’ or ‘occupation’), the Yes Men impersonating the Dow Chemical website, Ubermorgen creating a website where US citizens could sell their vote in the 2000 election, the proto-social media of Life Sharing (2000) by the artist duo 0100101110101101.org, who made the contents of their home computer public for three years. The recorded or preserved examples skew towards the tastes and political persuasion of artworld curators and activists.[5] One significant contemporary act of canonization was the ‘net.art’ exhibition in Berlin in 1995 organized by Pit Schultz, founder of the nettime mailing list, which brought a group of European artists, including Jodi and Alexei Shulgin, under a shared movement. What brought these diverse artists together, according to Schultz, was their resistance to the naive utopianism of the Californian Ideology, the idea promulgated by Wired magazine that ‘in the digital utopia, everybody will be both hip and rich.’ Schultz wrote that ‘Against the expectation of early adopters, Big Internet is creating a new mass of “users,” who just shut up and click’. The Dot-com bubble may have burst in 2000, but not through the efforts of the net artists, and the corporate survivors of the bust created a new boom through onboarding the world to their services. By the early noughties, the net artists had lost, though their dissident activities might have been more an artworld spectacle than any credible threat to corporate hegemony.

IV.

Not without reason, then, does the artworld speak of net art in the past tense. ‘Net art (or Internet art),’ we read on the art brokerage site artsy.net, ‘describes work made in the 1990s through the early 2000s that uses the Internet as a primary medium.’ Among curators, galleries, and art schools, net art has given way to the agnosticism of ‘new media art’ to ‘computational art’—a putative ‘creative’ complement to computational science—and to the complacency of ‘post-internet art.’[6] All three negate the hypothesis of internet-induced rupture on the familiar institutional pattern of pluralism and post-ism, with a dash of creative industries poptimism or Mark Fisher inflected depression. Opposite such resignation in the face of a world-historical event, characteristic of academies and all manners of incumbents, is the crux of net art, which is the crux of all true avant-gardes: the freeing of a new technology from the straitjacket of old concepts and mores. Thus net art isn’t ‘art on the internet’ or ‘art about the internet’[7]—‘medium’ as material and ‘content’ as moral being critical concepts that hinder aesthetic understanding. What might further it is form, for net art seeks to give form, and thereby intelligibility, to a phenomenological shift precipitated by technological change.[8] More ambitiously, net art can be said to be devoted to the production of new entities, egregores, and ultimately, the metaverse, AGI, technological singularity.

V.

The internet is no longer a ‘new’ medium, it is a mass medium, though not on the old model of a one-to-many delivery system. While the early net artists may have had higher hopes for online enfranchisement, internet ‘users’ of today are nodes in a network in which any rigid distinction between producer and consumer has been obliterated. Freed from an imputed paradigm of performative anti-corporate activism, we can recognize a new net art: posting as art, post-authorship and collective works, high interactivity and connection, algorithmic hijacking, ‘lefthand’ style and outsider art. The praxis of new net art lowers the bar for production: its stance against authorship and attribution allows users to simply copy and paste content. Anonymity and pseudonymity unmoor signifiers from any morally or legally recognized signified, any humanistic unit, be it citizen or person or self. The point is not for some prior entity to acquire capital, whether monetary or social, but for content to circulate, to become meme. Consumption takes on the active character of sharing, liking, replying – all the micro-actions summed by the term ‘engagement.’ Aesthetically, new net art occupies a parodic space that constantly baits earnest and hysterical engagement. It’s giving special attention to internet-native forms, profile pictures, memes, hypercitation, and the attendant rabbitholes they create for users. If the best net artists of the nineties, such as Jodi, were HTML and CSS hackers who displayed their aberrant creations, then the new net artists are doing the same for the social media feed (alt posting, Chineseposting, copypasta) and crypto (right-click save, auctions, reserve backed NFTs). Misdirecting users through rogue links and phishing has given way to algorithmic manipulation in the age of the timeline.

VI.

Between the nineties and its present resurgence, during the decade-and-a-half of sclerotic artworld attempts to assimilate the internet into its gallery and collection paradigms, the practices and ethos of new net art were being developed on imageboards. Brad Troemel observed in 2010 that the ‘most advanced’ aesthetic theory promulgated by a mainstream curator – Nicolas Bourriaud’s Relational Aesthetics – had its most exemplary instantiations not in white cube galleries but on the disreputable 4Chan.[9] Bourriaud’s theory is, like all aesthetic theory, at once descriptive and normative. Its point of departure was a growing preoccupation among traditional gallery artists with artistic practices ‘which take as their theoretical and practical point of departure the whole of human relations and their social context.’ This is meant to contrast with art that emphasizes private contemplation and/or exists in an independent aesthetic realm. The pieces he mentions don’t explicitly stray far from the format of a sixties Happening: a dinner organized in a collector’s home, an artist working as a supermarket cashier for a week, a gym workshop held in a gallery. While Bourriaud’s theory doesn’t emerge from a consideration of the internet explicitly, his animating concern provides a succinct articulation of the communication technology pessimism undergirding both early net art and its various artworld successors. In the foreword to his book Relational Aesthetics (1998), Bourriaud compares the effects of communication technology with those of the motorway: like motorways which speed up journeys at the cost of serendipitous discovery, ‘communication superhighways’ have a similar effect on social relationships, making certain standardized interactions more efficient at the cost of spontaneity and freedom. Thus he rescues a swath of mundane performance art from banality by claiming they ‘open up’ some modest social possibilities apparently foreclosed by his Frankfurt school-inflected diagnosis of totalising reification. Troemel criticises Bourriaud’s chosen examples for falling short of his own ideal of a collaborative, social art: they were all performed by individual ‘art stars,’ often in galleries, and always with an eye towards curators and collectors. Their interactivity was more a gimmick than a genuine practice. 4Chan, he argues instead, with particular mention of the /b/ message board and the 2009 mARBLECAKEALSOTHEGAME raid,[10] is exemplary of relational aesthetics in its group production of memes and its attendant collapse of the ‘viewer/creator dichotomy.’

VII.

Some other precursors of net art: pseudepigrapha, works falsely attributed to a figure of the past, such as the seventeenth century sex and midwifery manual Aristotle’s Masterpiece, or the works of a 5th–6th century Greek theologian and neoplatonist, his real name lost to history, who styled himself as Dionysius the Areopagite, the first century Athenian convert to Christianity; the anonymous lampoons mocking kings, princes and governors circulating regularly following the invention of the printing press; the Republic of Letters, a long-distance, correspondence-based intellectual community of the seventeenth and eighteenth century. What is required is a system that can transmit arbitrary messages over arbitrary distances: books, letters, parcels, ambassadors, messages in bottles, the vagaries of history–yes; smoke signals, semaphore, homing pigeons, pneumatic mail, underground rail—no.[11]

VIII.

While the new wave of net art shares a conviction with its predecessor in the momentous and untapped potential of the internet, it has more in common with the praxis of a different art movement of the nineties. Neoism, a parodistic -ism, was a loose underground movement active in the eighties that pioneered the use of open pseudonyms such as the ‘open pop star’ Monty Cantsin. This gave rise in the nineties to an influential offshoot, the open pseudonym of Luther Blissett under which an anonymous collective wrote the popular novel Q (1999).[12] Succeeding this was the breakaway Wu Ming writer’s collective, ‘Wu Ming’ (being Chinese for ‘anonymous’), pioneering a precursor to Chineseposting, with its logogrammatic compression and neo-Orientalist acknowledgement of mutually assured technological acceleration, not to mention the arbitrage opportunity of reposting content from the closed Chinese internet.

IX.

New net art is attempting to make good on the Landian claim of art as ‘irrational surplus, or the ineliminable and beautiful danger of unconscious creative energy: nature with fangs.’[13] The ‘Warholian group chat’—Hot Pot—that gave rise to the new net art collective Remilia was designed to act as a virtual factory optimized for collective creativity, a hive-mind producing tweets to be stolen and reposted, like a sped-up exquisite corpse or socialized automatic writing. This approximates the outside to the orderly nomological Enlightenment universe of Newton, the ‘trauma’ of Kant’s third critique: nature not as a system of laws, as a cosmos that abhors vacuum, that prefers the shortest path, but nature as generative chaos, as immanent God. Against any Protestant imputation of forgotten labor, Hegel’s Speculative Reason mopping up ‘the slaughter bench of history’ being the greatest example, new net art advocates having fun online. This sets it apart from those new media and post-internet artists who seek to impose seriousness onto playful online interactions, such as the later works of 0100101110101101.org, eg Freedom (2010), a counterstrike performance where the authors asked other players not to kill them because they’re an artist, or No Fun (2010) where the artists played Chatroulette as a hanged man.

X.

‘Whoever is losing their sense of humour fastest is losing.’[14] Humour is the critical complement of fun and play—it deflates pompous and gaseous ideas. It’s thus no coincidence that the Remilia manifesto for new net art is structured like a joke, ending with the punchline ‘interns wrote this post.’[15] Departing from a nineteenth-century paradigm of avant-garde and political tactics – the manifesto as a catechism, a coordination mechanism for collective action—new net art, according to Remilia, is built on more lighthearted association of personas rather than persons, like that represented by 4Chan, whose admission criteria are semiotical—an understanding of lore and posting style—rather than credentialistic. The difference between 4Chan and the new wave is one of attitude: the former is characterized by ostracism, rage, and pessimism, while the latter is optimistic, wholesome, ‘whitepilled.’ It’s the difference between a sexually resentful, unemployed Underground Man and an aristocratic NEET waging information war and building parallel institutions. The difference between a post-internet artist such as Troemel and the new wave is one of theology. Troemel cites Dominick Chen’s claim that ‘as long as there exists an asymmetry (or distance) between producer and receiver, the modality of cultural production would inevitably lead back to a religious power structure.’ The implied virtue of a relational aesthetic is its secularising, egalitarian tendency, which in Troemel’s own artistic practice is cashed out as incessant political trolling, an Adornian negative dialectic. This isn’t fun insofar as it’s beholden to its object of critique, falling into the common atheist trap of idolatry.[16] The new wave recognises that the anti-clericalism inherent in internet cultures such as 4Chan doesn’t imply atheism or a Rousseauian social progressivism. The immanent, retro-chronological theology of Nick Land, comes closer to articulating an axiology and metaphysics constructive to online interaction and technological development. It offers the loser 4Chan Hikikomori or the artworld troll an opportunity to raise their profile and restyle themselves as angels of Capital acceleration, agents of cybernetic positive feedback.

XI.

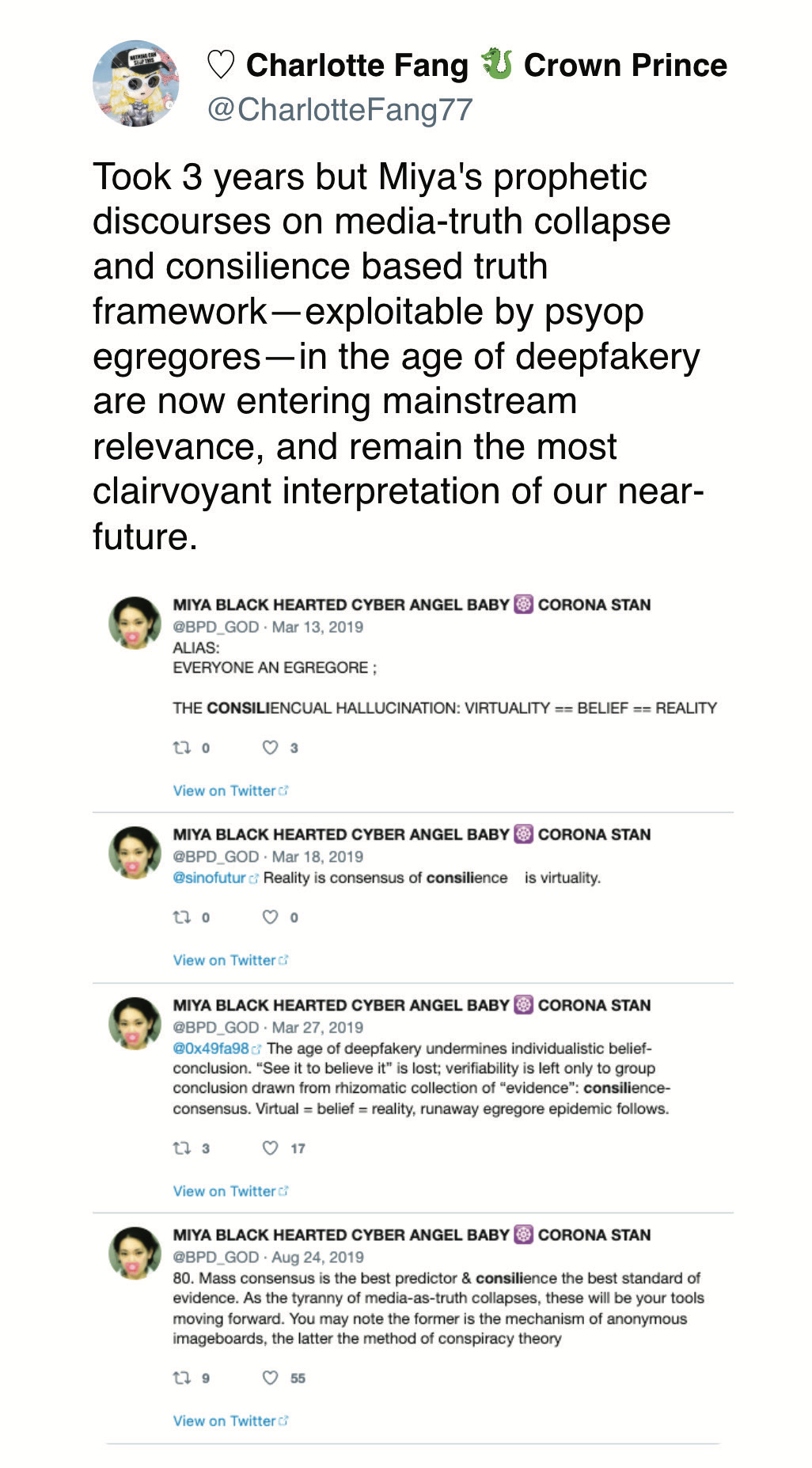

The aesthetics of the internet imply an epistemology, a stance with respect to how things can be known. The information superhighway, with its cables, grids, and matrices, rendered cinematically as early as Tron (1982), has given way aesthetically to the photorealistic paradigm of video games and the skeuomorphism of the first few generations of the iPhone operating system. Gibson’s cyberworld has been hidden behind colourful, animated interfaces steeped in mimetic content, in photos and videos and three dimensional virtual worlds. The epistemic consequences of this aesthetic shift are best illustrated by the revival of global scepticism, the Cartesian possibility of total and systematic deception, through the film The Matrix (1999), summarized in its conceit of the ‘red pill’ and the ‘blue pill’: the choice between learning an unsettling truth and having a comforting lie affirmed. Instead of the dubious, sophomore dichotomy of virtual and physical reality, the red-pill-and-blue-pill meme is more often cashed out in postmodern terms of narratives and the interests they serve, ‘reality’ being whatever story or slogan commands consensus. If a seventeenth-century prince had to improvise his actions much of the time owing to slow and leaky horse-based communication channels, the contemporary internet user suffers from the opposite problem of information overload that precludes reflection and understanding.[17] The epistemic paradigm of verification, where claims are checked by individuals against evidence (images, videos, witnesses, ‘sources’), is easily hijacked by deepfakes and shitposters. Where traditional authorities respond to ‘misinformation’ with cynical appeals to ‘expertise’ and by imposing Schmittian states of exception, new net art responds to ‘post-truth’ scepticism through an epistemology of consilience, where ecumenical, interdisciplinary convergence is taken as a truth signal.[18] With its ethos of freeing information flows from the obstacles of censorship imposed by institutions, externally, and by the ego from within, new net art approaches a Feyerabendian epistemic anarchy with its conviction that truth will win in a free marketplace of ideas. If the posting style of new net art tends towards irony, towards ambivalent statements, this doesn’t undermine its truth-seeking orientation; it isn’t ‘millennial’ irony described by David Foster Wallace, with its inherent neuroticism and preemptive defensiveness, its ingratiating, handwavy, scientistic scepticism.[19] It’s a playful irony that holds that truth is more likely to emerge from a joke, a flippant statement, a suggestion, a footnote—coherence be damned—than a serious, official narrative.

XII.

Why is net art having a resurgence? The artist and curator Jon Ippolito wrote in 2002 that internet art was being held back by the absence of a mechanism to sell digital assets.[20] The present revival of internet art can thus partially be attributed to the rapid adoption of Non-Fungible Token standards in 2020 and the attendant influx of capital. While this has created a proliferation of ‘rugcore’ aesthetics, low effort scam projects, it has also launched and legitimized the new net art movement. Another contemporaneous factor were the lockdowns during the pandemic years of 2020–21, which redirected practically all social interactions through online interfaces. The ambient presence of the internet on which the post-internet movement rested was transformed into uncomfortable salience. The stakes have become too high to leave the fate of the internet to Silicon Valley and governments. And so net art is coming back, richer, less naive, faster, freer, more social and more fun.

Nick Land, "Art as Insurrection" (1991), collected in "Fanged Noumena" (2011), pp. 145-174 ↩︎

Morphologically close, but etymologically and semantically unrelated to 'emoticon.' ↩︎

Anachronistically, we can call aspects of these mimeographed and photocopied pieces 'lefthand' style. ↩︎

Consider Rhizome.orgʼs “Net Art Anthology" which “identifies, preserves, and presents 100 exemplary works" of net art. The anthology takes a broad interpretation of ʻnet artʼ to include post-internet art and exhibits a bias [21]towards works preoccupied with orthodox political activism. ↩︎

“Any hope for the Internet to make things easier, to reduce the anxiety of my existence, was simply over ‒ it failed ‒ and it was just another thing to deal with” wrote Gene McHugh on his blog Post Internet in 2010. ↩︎

Early net artist Josephine Bosma defines net art as ʻart based in or on Internet cultures […] Net artʼs basis in Internet cultures means that a physical (hardwired or wireless) connection to the Internet is not necessary in individual net art works. A net art work can exist completely outside of the Net […] The ʻnetʼ in net art is both a social and a tech-nological reference ('the networkʼ) (see Josephine Bosma, “Nettitudes: Let's Talk Net Art" (2011), p. 24). ʻThe netʼ is a social and technological reference, but Bosmaʼs definition of internet art in terms of internet cultures is circular as it leaves the key term ‒ ʻartʼ ‒ undefined. Not everything produced by or based on an ʻinternet cultureʼ is net art, unless we want to count a book like Angela Nagleʼs Kill All Normies as net art. In order to make her definition work, Bosma falls back on the concept that art is whatever is produced by a self-conscious artist. ↩︎

The same can be said, as a test of this claim, about surrealism, which employed the new technology of film and photography, and about impressionism, which reacted against the same. ↩︎

Brad Troemel, “What Relation Aesthetics Can Learn From 4Chan" (2011), collected in “Peer Pressure: Essays on the Internet by an Artist on the Internet“, p. 9-17 ↩︎

The mARBLECAKEALSOTHEGAME raid involved posters using sophisticated ballot-stuffing software programmes to propel 4Chanʼs founder m00t to the top of TIME Magazineʼs list of 100 Most Influential People. ↩︎

Counterfactually one may speculate on the proto-networked art that wasn’t (or wasn’t preserved), such as telegraph art or fax art. ↩︎

Examples of new wave ʻopen pop starsʼ are the Twitter clones of Angelicism01, Miya, and Tarquin X. ↩︎

Nick Land, “Art as Insurrection" (1991), collected in “Fanged Noumena" (2011), p. 151 ↩︎

Taken from Nick Land posting on Twitter as @Outsideness at 5:50 PM GMT, Feb. 4, 2018 ↩︎

See Appendix A: What Remilia Believes In ↩︎

As Nietzsche says in The Gay Science, choosing oneʼs antipodes is more important than oneʼs friends. The Devil is a better antipode than artworld institutions, especially if oneʼs trolling is of a kind that increases oneʼs standing in those very institutions. ↩︎

The outcome is the same: improvization. ↩︎

A good example of millennial irony is attributed to Jia Tolentino by Lauren Oyler in her review of Trick Mirror in the London Review of Books. The same kind of preemptive, defensive irony is then displayed in Oylerʼs own ʻinternetʼ novel, Fake Accounts, presumably ironically. ↩︎

Ippolito, Jon [2002]: ʻTen Myths of Internet Artʼ, in Leonardo 25 (5). ↩︎

The avant-garde is faced with the problem of accumulating prestige, which requires preservation, and living up to its ambition of eradicating the distinction between life and art, of being in the moment, enacting true happenings. Outsourcing the former to a cadre of curators and critics is a sensible division of labor, though it risks imbuing those gatekeepers of art with an excessive amount of power. ↩︎